The Whire Nile flows north from its origin in Lake Victoria in the Tanzania-Kenya-Uganda conjunction. The Blue Nile flows out of Lake Tana in Ethiopia. The rivers become the Nile at the wedding of the waters at Khartoum, Sudan.

The Whire Nile flows north from its origin in Lake Victoria in the Tanzania-Kenya-Uganda conjunction. The Blue Nile flows out of Lake Tana in Ethiopia. The rivers become the Nile at the wedding of the waters at Khartoum, Sudan.

From an early age, looking at the pictures in National Geographic magazine I had been fascinated with ancient Egypt and boats on the Nile.

My dream came true.

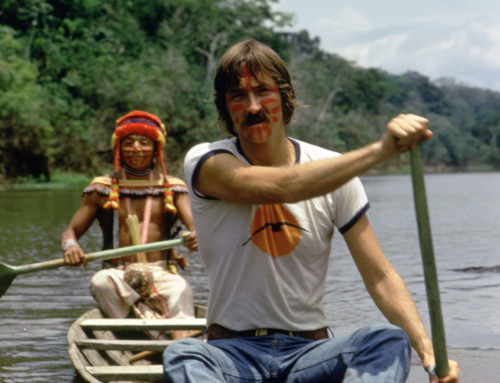

Cherif and I started our journey outside Wad Medani, Sudan, in the Blue Nile. We rode to the river on a donkey cart. Sixteen bags and two men transformed into boats and two men.

I’d met Cherif Zaouch during a climbing, trekking and canoeing adventure I was leading for schizophrenics on the Appalachian Trail. He was a Tunisian, and a personal friend of the director of Earth House, a place that assisted schizophrenics to recovery. My Earth Adventure program became part of the treatment.

Earth Adventure inspired Cherif. “Let’s do an adventure.” He invited me to visit him in Tunisia and ride horses over the desert to Morocco. I made a counteroffer – a kayak journey on the Nile – and the trip was on.

I’ve always been fascinated by the statement,

“You Can’t Do It”.

In my initial research, I discovered a hidden risk in the water of the Nile. It was a microscopic leech, which after attaching itself to human skin, made its way through the skin into the bloodstream, undetected, and usually lodged in the urinary bladder. The evidence of blood in the urine came from the fragments of broken egg cutting tissue, which came from the leech, that now had turned into a worm.

The disease is called bilharzia named after Theodore Bilharz who discovered the condition in 1856. Yet there is evidence in ancient wrìtings that the condition has been around for thousands of years. The medicine to treat the disease, to eliminate the worm living inside the host, is an arsenic type which sometimes causes a psychotic break, often ending in suicide.

Doctors I interviewed in London, New York, Miami, and San Francisco who knew about the disease strongly suggested I take OIL another challenge.

Avoiding the disease became a challenge in itself.

I discovered the leech had two hosts it fed on. The first was a snail; humans were the second. The snail lived on vegetation and usually in stagnant water. This meant it lived mainly in irrigation canals along the Nile. I would be careful getting in and out of the boat, drink the water from the middle of the river and stay out of the canals.

I ended up spending months on the Nile, and never contracted the disease.

One of the most powerful aspects of the Nile is its seeming changelessness. In modern times, the great river has been civilized and controlled, chiefly by the mammoth darn at Aswan, yet throughout our journey J was struck by its quality of wildness almost untouched by the five thousand years of history lining its banks.

The chugging of the diesel-driven water pumps redistributing Nile water to farmland ditches in the Sudan was a hint of modern technology. But most of the water pumps in Egypt were powered by camels or oxen walking in a circle as the century old machinery dipped earthenware pots into the river then spilled the Life giving substance into the ditches. The land, the people, the dress, the dwellings all looked as if it were still in the Old Testament.

The Emperor Nero’s centurions came up the Nile, trying to find its source and the origin o1 Africa’s gold. Many explorers, including my hero Sir Richard Burton (the 19th century explorer, writer and intellectual), failed in their search for the source of the Nile. Herodotus traveled the river in search of strange and compelling stories for his histories. Many of its voyagers, both ancient and modern, have spoken feelingly of the mighty river’s impact on mind and body. As Alan Moorehead wrote in The White Nile, “It is a never-ending flood of warm, life-giving water that spans half of Africa from the equator to the Mediterranean, and it is still the mightiest river on the earth.”

We passed Khartoum in the Blue Nile slowly. Cherifcomplained, “David, you have got me in a lake.” Admittedly, I thought the river would race us on the surface much faster. As the Blue Nile began its turn north toward Egypt, we glimpsed the White Nile ahead to our left. By keeping up our steady paddling we placed ourselves along the line of the confluence of the two rivers. The waters did not unite easily. The White Nile was a muddy grey around my left paddle; the Blue Nile ‘as greenish on my right. I could feel the split of energies, the vast differences in their sources.

As the sun began to set, we paddled over to a sand dune island and set up our dome-shaped tent. When we had everything set up, the arched doorway of the tent framed a mosque across the river. I zipped down the back window and immediately saw a pirogue, a kind of roughly built Nile fishing boat, bearing down on the island.

“Uh-oh,” I said to Cherif, “We’ve got visitors.” I’d been in civilized environments too long, with their fears and prejudices, to be clear in the mind. We were eating bread, honey, and olive oil when the boat ground to a halt on the beach in front of us. In it vere a couple of tough-looking fellows who had tracked us from Khartoum. We continued to eat hut tensed up a hit as they approached.

The men jumped onto the beach.

“You drop this,” one of them said.

It was one of our smaller packs, which Cherif had left on the bank near Khartoum. Our visitors dined with us on hard-boiled eggs, olive oil, onions, garlic, breadsticks, oranges, and a handful of almonds. As they left for Khartoum, we hugged each other happily.

“These Nubians are honest people,” I said.

“That is why the Babylonians made such good slaves out of them,” Cherif replied.

Our next days on the Nile were a fusion of time. The river was slow. Sometimes wind from the north drove us backward against the current. One by one, our connections with the outside world dripped away, and our sense of place and time eroded…but not without a struggle, and not without accompanying stress.

The stress of being on the river was more than physical. There was stress generated by the attendant unknowns of our journey – Lingering anxieties concerning the people we would encounter along the way, the crocodiles that might pose a danger and the constant threat of bilharzia.

I love the “discovery” aspect of adventure. Part of that discovery is finding out what is illusion and what is real. It can be difficult to let go of what one believes to be true. Face it, we carry the belief with us and we are totally convinced it is true until it is proved otherwise. Sometimes we hold on even though it is proven wrong. It’s too painful to let go of a belief held so long.

In time we let go of all the unknown stresses. My watch stopped the first day. We became aware and confident in our environment. We realized the Nubians were extremely honest, that the crocodiles hanging out on the beach were only driftwood logs, and that the microscopic leech didn’t swim in the main part of the river.The physical stress of the trip was ultimately a catalyst for change. At the start of our journey I noticed Cherif’s flabby triceps. In thirty days his body had been transformed; it was lean, brown, and toughened. My shoulder muscles started to bulge. We were up with the sun each morning, then thirty minutes of yoga followed by a short run. Cherif acknowledged the excitement and fun of running particularly down the sand dunes.

“David!” Cherif shouted, “You should teach the Tunisian Army is type of conditioning.”

Breakfast consisted of Sudanese flat bread, tahini, honey and dates. We drank the water from the Nile. We paddled ten hours on some days. After months, the river was flowing like wine.

Near Shendi, we saw two men working with a net stretched across a pond on an island close to shore. The water was shallow enough to wade, so we investigated. By this time we’d moved beyond our fear ofexposing our bodies to the water.

The men were crocodile hunting. They showed us the tracks and said that if they were lucky, the crocodile would be in the net within a couple of days. Men had been hunting crocodiles like this for six thousand years – no change. No need to change. We drank tea with the Croc-hunrers and ate steved fish on their boat. “We live on the Nile; all our lives are here, at this place, here”, one told us.

The scenery along the river was wonderful; a slow-moving phantasmagoria of sand dunes, palms, steep cliffs, banana trees, and brilliant colors as the sun changed position. In the evenings we watched the flight of cranes decorating the crimson glass of the river. We heard the constant sigh of the wind and the continuous chugging of water pumps. People waved to us everywhere, and children ran along the banks to keep up with our boats. They had never seen kayaks before, but they were not frightened. Villagers all along the Nile invited us ashore and into their houses to drink tea, to eat, to sleep – whatever we wanted. They were secure in their place on the river.

It reminded me of the contentment that reigned in the great city built by Pharaoh Ramses I, as described by a thirteenth-century BC Egyptian poet:

“Its fields arc full of all good things and it has provisions and sustenance every day. Its channels abound in fish and its lakes in birds. Its plots arc green with herbage and its banks bear dates. Its granaries are overflowing with barley and wheat and they reach unto the sky. Fruits and fish are there for sustenance and wine from the vinyards of Kamkeme surpassing honey. He who dwells there is happy; and there the humble man is like the great elsewhere.”

For the most part the Nile was flat with one-foot waves produced by the wind. The north wind was the single biggest obstacle. Smack in our face we had to paddle against it for many days . Admittedly, it was rather depressing trave1ing downriver yet being pushed back upriver when you stopped paddling. One day, the wind was so strong I was paddling in place. The wind pushed the how to one side and turned me around 180 degrees, so I was facing upriver. I looked over and saw Cherif walking along the shore, pulling his kayak by a rope.

It wasn’t all flat water, waves and wind. Our kayaks made of canvas and vood were not the kind that can careen through rapids and bounce off rocks. The rapids took our journey to a whole other level of excitement. It was a huge hassle to portage around the rapids, yet we didn’t want to wreck our Im)de of transportation.

At one point, children motioned us with a “Come here” hand gesture. We continued paddling. Practically everyone throughout the journey did the same gesture. If we stopped every time this happened, we’d still be there. These children immediately started running along the banks yelling. Cherif couldn’t understand them until it was too late. We were sucked into the flow of rapids, too far, from shore to get out.

I didn’t have time to put on the spray-skirt that keeps the river out of the kayak. The ride was quite straightforward with a simple strategy: keep the nose going in the direction of the water, stay off the rocks, and use the paddle blades for balance. I hit the churning water with a yell and went into the rollercoaster ride. The river poured over the bow and engulfed the boat and me up to my chest. The next moment the kayak shot skyward and it was over.

The river was once again smooth and slow. ‘I think those kids were trying to tell us something,” I shouted at Cherif. He was all smiles. If the river traveled this fast, we’d he in Cairo in no time.

Cherif’s sturdier kayak made it through unharmed. My kayak was filling with water. Hapi got her first set of injuries. I took everything out, turned her over, patched the holes with tape and we were back on the river.

The next set of rapids happened a few days later. It was early morning and we heard the noise. This time we parked the kayaks in order to take a survey. It looked runnable. Of course what did I know? Cherif went for his helmet. I went for the rapids.

These sea-going, expedition kayaks are not designed to turn quickly nor bounce off rocks. They are more stable than their sister slalom kayaks that can turn by one strong stroke. The rapid-running kayak is powered by the speed of the river and more or less steered by paddling. The sea-going, long distance kayak is powered by the paddler ant] tracks straight-ahead rather than moving to the side by each stroke.

The rapids were bouncy, fun and I avoided the rocks. At the bottom of the set, I turned up-river to watch Cherif. There was a crocodile two feet oft the right, alongside my kayak. I’d always associated this pre-historic creature with beaches and still-water, yet later I learned that they often wait below rapids for food to wash through. The crocodile slowly submerged out of sight as I quickly paddled backwards. I thought about Cherif. If he flips the kayak, that helmet won’t help against the jaws of the croc.

Fortunately Cherif ran the rapids without capsizing. The next set of rapids was different. A few hundred yards ahead of Cherif, I heard the roar. I saw the drop. The first fall plunged me a dozen feet, then the kayak rushed through another fifty feet of white water, bouncing wildly, its wooden dowels cracking. Through a blaze of spray in the hot air I yelled, “Keep going, Hapi! Stick together, baby!” Of course I was telling myself the same thing. When I could see again I saw Cherif was just entering the center fall. He stayed up for a few seconds, and then he was flipped over. I heard him yelling.

It was a mess. Cherif got to his overturned boat, and I saw him struggling to the beach. I spun around, picking up his hat, canteen, date jars, shaving kit, plastic container, water pail, and some clay water cooling jars. Eventually I got all the stuff together and made it over to the beach. I checked the boat again for holes. None. Good. There were some had scrapes and broken wood on Cherif’s boat, hut the bottom of his boat was made of thick rubber. He said he’d rolled over as soon as he hit the bottom of the spillway to avoid a rock. He got out from under the boat while he was still underwater and kept the boat off the rocks.

He was very high.

“I remember every detail,” he said excitedly. “After I got out I didn’t let go. I was trying to stuff back the things that were coming out of the boat.” His rudder was bent, and he straightened it with a rock.

I was high, too. I wanted to go back over that fall. I asked Cherif if I could use his kayak because it was empty. “Are you serious?” So I emptied Hapi and took her out. She felt very light all of a sudden. I started paddling toward the great spillway. But then something spoke to me: “You had your ride. Don’t be greedy.”

The weeks turned to months. Cherif and I parted ways in Aswan in southern Egypt. I paddled the Egyptian stretch of the Nile solo.

The river after the High Aswan Dam was fast and filthy. It was interesting to see the different techniques women used to collect water from the river. One way was to submerge the large clay pot, letting the water with its surface scum rush into the container. Another technique was to hit the water with the side of the pot creating an opening in the scum before submerging the pot. A third way was to hit the water by hand then push the pot into the opening. I boiled the Egyptian Nile water on a small gas stove between my legs as I paddled. I carefully poured the water from the pot into plastic containers to cool. The tiny carcasses of the critters boiled were returned to the river.

The ancient Egyptian buildings, temples, pyramids, sculptures were magnificent. From Ramses’ Abu Simbel to the great pyramids, the banks of the Nile are outdoor museums of antiquity that we have all seen in travel photos and films. Being there makes it so real.

It had always been in the back of my mind to climb the great pyramid at Giza, and as it turned out, this marked the symbolic end of the Nile journey.

The face of Cheops’ pyramid, ten miles west of Cairo, was far from smooth. After a thirteenth-century earthquake cracked the face, the builders of nearby cities had used the pyramid as a quarry for the Tura limestone that once covered it. Some of the blocks at the base were as big as I was, and I had to use my arms to pull myself up. I zigzagged; keeping up a rhythm that was like running.

I was climbing on a monument that had taken seventy years and the sweat of twenty thousand to build. It was an ascent out of one consciousness and into another. The city of Cairo showed faintly, its towers and minarets rising form the pollution. I could see half a dozen more pyramids at Memphis and Saqqara. I sat down cross-legged on the square platform that was created when the triangular cap of the structure was stolen away.

I gazed out into the Sahara. I had never seen such a grand view of my planet. I no longer felt the burning rays on my almost black skin. Ra’s sun spun overhead and then down toward the sands to the west, toward Morocco, where I had first felt the presence of the source.

I gazed out into the Sahara. I had never seen such a grand view of my planet. I no longer felt the burning rays on my almost black skin. Ra’s sun spun overhead and then down toward the sands to the west, toward Morocco, where I had first felt the presence of the source.

The sun of this land is life-giving; the ancients lived by it, sustained by the sun god, Ra, who gave them greatness in accord with their great river. Let the light shine through. Use the sun.

I fell into a meditation. Soon darkness stole up the slopes of the pyramid, without my sensing the true end of the day. As I came out of the meditation, a message came to me, “Heal.”

And so it was on the Nile that I verified my true purpose – Healing.

Before and after this journey, I have devoted my life to uplifting peoples’ lives, by allowing them to touch something inside, in order to get fit, reach goals, and realize the fullness of life.